American author Ernest Hemingway committed suicide in 1961, not long after being administered electroconvulsive shock therapy at the Mayo Clinic. He is reported to have said, “Well, what is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business? It was a brilliant cure but we lost the patient.” (Wikipedia).

Despite the notorious unreliability of memory, we are nothing without a sense of our past. As a writer, Hemingway would have travelled through his thoughts and past experiences, relying on what he remembered as a computer relies upon a databank. Of course, what he, or any writer, attempts to achieve is a sense of intrinsic truth, rather than quantifiable variables. The emotional connections we form to the spaces, people, and events around us are significantly important in how—or even if—a retrievable memory is formed.

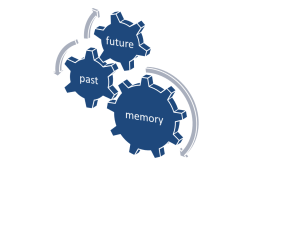

The significance and meaning of our past experiences are unstable for a significant reason; the flexibility, rather than fixed state of our memory allows us to re-interpret, negotiate understanding, and reuse the data of our memories to aid us in our decision-making for the future.

For many writers and readers, the flexibility of memory can cause anxiety, and worry about ‘the truth’ of story-telling. Memoir writing and autobiography is often held to critical scrutiny in public conversations about the accuracy of the text.

A similar apprehension exists about the truth and accuracy of historically-based works; however, even in the academic tradition history is a varied and complicated set of perspectives subject to fierce debate. Introducing fictional elements within historical truths can create a back-lash of criticism.

The urge to classify written text into genres is probably deeply connected to how we feel about “the truth” in writing. John Mendelsohn, in an essay on the history of memoir in New Yorker in 2010, writes, “the reactions to phony memoirs often tell us more about the tangled issues of veracity, mendacity, history, and politics than the books themselves do” (“But Enough About Me: What does the Popularity of Memoirs Tell us About Ourselves?”). We tend to differentiate between a truthfulness universally experienced and an honesty about individual reality, often demanding stricter standards for truth-telling in “real” stories.

However, culturally and individually, we were never made to be faithful to the past, or whatever truths have been lost to time. In the contemplation of traditions, the very language itself demonstrates this conflicting urge to retain a relationship with the past, but to also be unfaithful to it. From the Latin, traditio, tradition means “a custom, opinion, or belief handed down to posterity… this process of handing down.” Traditio from tradere means “hand on, betray”. The noun, traditor, from tradere refers to “an early Christian who surrendered copies of Scripture or Church property to his or her persecutors to save his or her life.” Thus, the origin of ‘traitor.’ (OED).

Even though we may have lost some our cultural awareness about the duality of meaning of the word tradition, we have a sense of it when we think of how the word has evolved from handing on, or betraying to save one’s self, to handing down to preserve for posterity. Our cultural, collective memories (like our individual ones) are a time machine that not only moves through the past, but also passes through a warp of alternate possibilities, creating emotional and adaptive (often unconscious) deviations from the original.

The simple act of thinking back can create a butterfly effect, and even while the results are sometimes difficult to measure, the effect is always present, always at play. Perhaps Kierkegaard argued it best when he suggested that repetition is more about moving away from origins than it is about remaining at the origin. By simply remembering we dislocate further from the primary incident, eventually moving so far away that the memory of original context becomes lost, changing meaning and relevancy in significant ways.

For a writer, the failure of literal memory is a creative space in which possibilities emerge. After all, if I wrote a story about the significant symbols and metaphors of my life, without showing the reader how to adjust to my world or to learn how to relate, no one would understand my story. We simply would remain too autonomous to communicate, and yet, we are bound to a collective experience of life; language is the medium in which we meet. But before we enter this collective space, we must pass through the gap that effaces, for the moment, our singularity.

In the way that we transform our unique experiences into a communal language, becoming for a moment a creature like Seven of Nine of Star Trek, we also relinquish our memories in the process of expressing them. Mendelsohn writes,

As for Freud’s charge that memoirs are flawed by mendacity, it may be that the culprit here is not really the memoir genre but simply memory itself. … a seemingly inborn desire on the part of Homo sapiens for coherent narratives, for meaning, often warps the way we remember things.

Claudia Hammond argues that the flexibility of memory also enables us to piece together our past into new form so we may imagine our future possibilities. Drawing from studies of memory loss, she argues that people without memories do not have a sense of their future, and are greatly inhibited in making decisions, or even caring about what will happen next.

I would suggest that no great trauma needs to occur for us to lose pieces of memory, that if we don’t cultivate our identity by revisiting the past, we block ourselves from seeing our choices and considering their importance to us. This is to say, if we surrender our own identity-making process by refusing to look back—perhaps by repressing negative experiences or by living nostalgically—we lose our balance with our present reality. We forget how to properly evaluate a situation (for lack of sufficient or reliable data) and we are unable to make decisions about what to do next. We become stuck, afraid to risk moving forward. Living nostalgically, with a staunch belief that nothing bad can happen to us, we too easily ‘go-with-the-flow’ and imitate what others do. Unfortunately, failing to question, or think for ourselves can leave us extremely vulnerable to be taken advantage of by others.

I think Adrienne Rich said this best, “The unconscious wants truth. It ceases to speak to those who want something else more than truth.”

In creative work, like writing, the fastest way to block ourselves is to ignore what Rich calls ‘truth.’ Perhaps ‘truth’ is more accurately described as a way of remembering which is neither nostalgic nor repressive, but balanced and realistic. Creativity-promoters, like Julia Cameron and Robert Olen Butler have made names for themselves by promoting the writer’s deeper relationship with the subconscious self. Cameron has built a franchise on creating, delivering and promoting programs of ‘artistic rediscovery.’ Her program, like Butler’s creative writing class, rely on the exploration of memory to help dislodge blocks and engage the imagination.

It takes effort to cultivate awareness of ourselves, but if you are a writer, you probably already know that the most direct cure for writer’s block is to write. As other writers (like Pat Schneider, Anne Lamont) suggest in their how-to-books, write through pain, and keep on going, don’t stop because you’re likely to get stuck. The gist is, work through memory repression, and don’t get hung up on a utopian idea of what the past was. If the DeLorean from Back to the Future had never built up the speed, it would never have made that jump from the past to the future.

Our time machines can exist in many forms, the memories of others, books, video, and the landscapes in which we live. We take all of this data, and what exists within our own minds, and put these fragments together like a puzzle, negotiating the connections and determining their importance. What results is a narrative we can repeat, a story that is much less about the past than it is about the future.

We are constantly creating and recreating our narratives of identity, cultivating a sense of who we are and where we fit within our cultural contexts. We want to understand ourselves, and perhaps even more so, to be understood by others. I suspect our compulsion to record and save and archive everything arises from this keen desire to narrate our story to others, and find connection. Sometimes, when a dozen parents stand up in the front rows of the audience at the school play, videotaping their kids on stage, I wonder if we take this process too far. How much do we have to do before it becomes over-the-top data collection, which consumes us to the point of eclipsing experience (think of the sight-seers and tourists who spend more time clicking photos than admiring the landmarks). Why do we do it? Are we collecting evidence for some future narrative?

One sub-category of redemption narratives relies upon the mundane, routine process of recording as a means of supplying the truthfulness of other, more extraordinary revelations of the future. A.S. Byatt’s novel Possession is an example of the extremes of minutia, when small nuance and detail are set out like code leading good sleuths to larger discoveries of the self. Other examples of this thematic structure are present in the films Courage Under Fire, and People Like Us. In all three examples, technology of some sort (diary, audio recorder, home movie) plays an important role in the narrative arc of the story.

In real life, the process of data-collecting tends to be a slower collation of information and discovery. Light bulb moments rarely happen in the instant, and if we say they do, it is only because we’ve come to recognize the importance of particular moments only after a bit of time-travelling. The character, Doc in Back to the Future, demonstrates the instability of the ‘eureka moment,’ showing that relevance of our moments is gleaned from the backwards time-travelling process.

Doc recalls the day he invented time travel:

Marty visits Doc the day Doc invents time travel:

From real life, the much-exemplified story of Charles Darwin’s discovery of a theory of evolution was not a ‘eureka moment’ as Darwin himself later described. Rather, the theory of evolution was a process of revelation, one which Darwin’s journal notes had been engaged with for months before he understood the value of what he knew. If anything, this goes to show that memory-revision is deeply connected with the need to tell an engaging story that others can understand and will care about. We skip the boring stuff, and get right down to it.

Perhaps it is a fallacy of the time-travel genre to suggest the journey of time travel itself is instant. Travelling in time may be as lengthy a process as travelling across space. But then, what fun would it be, watching episode after episode of Doctor Who flying through time and space trapped within the Tardis?

Doctor Who (ironic) montage:

Writing a story is an unfolding of connection, one which requires tremendous flexibility of the imagination to create. If we travel back in time clinging to literal memory we tend to remain too rigid to discover the larger truth of the story. Meaningful details must fit together into something larger (like the montage of the video above), and it must hold an emotional truth for us. The presence of emotion in narratives acts like a glue, binding together the pieces into something that feels whole. Emotions can introduce a high level of unreliability to the veracity of memory, and as glue, they force a separation of the fragments which always contain the potential to destabilize the whole, remaining a future locus of rupture.

As we create our stories, the imperfection of memory, emotion, and language commingle, and no matter our intentions, meaning, and even truth, slips from our control. It seems that the price of being a visionary of our own lives requires a degree of falseness about our past, a necessity to which we all are susceptible. The time machine here is our memories, and we are forever travelling backward to change the course of our futures.

Courage Under Fire

People Like Us

Possession (slightly misleading trailer)

This is very interesting, and touches on a lot of topics that are very close to home for me. Have you ever read Frank Kermode’s Sense of an Ending? — He talks a lot about the influence of the temporal on the narrative. Although his larger points are a little different than what you are speaking about here, I think you would find some worth in his writing.

The role of ‘time machines’ as you have put it is something that I have thought and written about extensively, although in different terms. We look at the past nostalgically because it is clean. The memories, accurate or distorted (and they are always distorted in my opinion) take on a narrative structure. Because they now appear to have a narrative structure, they are loaded, like all narratives, with significance that is not actually inherent in the event. The present is a muddied mess –our beginnings are obscure, our endings are unknowable. When we look back we see cause-and-effect; beginning, middle, and end –we are lending ourselves to a delusion of temporal harmony that doesn’t really exist. Fiction, and all writing arguably, is the crafting of this harmony. If anything, “Truth” is buried deeper, but significance –a very real, functional significance –is brought up front and center.

This is a big topic. I hope I have not only rambled incoherently. I have many thoughts. Apologies for not taking the time to convey them more briefly! This was a great post, and I am looking forward to more from you.

LikeLike

I noticed you have some very interesting posts, which I’m looking forward to reading. I love your comment. It gives me much to consider.

The “time machine” here was inspired by an impromptu inter-blog challenge arising from the question of how the topic could apply in various fields/professions. This was where the challenge arose, with this post http://elkement.wordpress.com/2013/04/20/on-time-travelling-rigorous-categorization-of-science-fiction-movies/, and was brought up and responded to in the comments section. Another blogger also posted, http://theunemployedphilosophersblog.wordpress.com/2013/04/26/a-quickie-argument-against-determinism/ .

Thank you for suggesting Kermode’s text. I had been very curious about Northrop Frye’s discussion of the apocalyptic, and when I looked up Kermode on Amazon I’m reminded that he’s been recommended to me before. I think I’ll need to follow through on this now.

As for my ideas on nostalgia, I’m currently experiencing an upheaval in my prior thinking. My thoughts on memory have changed slightly from what they once were. I am very intrigued with the concept of a sanitized past, but am also aware of how cleansing can come at great cost to self and others. Perhaps I’ll gain better insight by considering the difference of ‘significance’ and ‘truth.’

I’ve been working on a novel that really grew out of ideas of memory and identity formation. I’ve sensed that there was something very workable in Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto.” Now that I’m moving into the third draft of the book, I’ve been revisiting this. Linda Hutcheon’s essay “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern” has become interesting to me in this context, as both essays intersect in their rejection of a uniform self existing in a utopian past.

I had chosen your cyborg posts to read next, and now I’m really looking forward to them. Thanks for sharing your thoughts.

LikeLike

I am so glad you are interested in my posts! They are, admittedly, hit or miss. I am first and foremost an aspiring novelist, writing in the genre of literary fiction. I started blogging as a way to practice writing and (hopefully) to gain a little readership. I choose topics I am interested in, but not necessarily an expert!

Thank you for bringing up Frye. I have not revisited his thoughts since university, and I am eager to now. I am also going to make a point to read Lunda Hutcheon’s essay. I have been thinking so much about these topics lately. I think they hold a pretty important space in my fiction, and dissecting them like this will make –I hope –for a novel with greater depth.

Thanks for following along on Chasing Wild Geese! I will look forward to more discussions!

LikeLike

My writing is literary fiction as well. Blogging, for me, began with a need to move past the discomfort of being public/published, and to practice writing. I also am aware of the pressure to “have a social media presence,” but I wanted to cultivate this on my own terms, and rather than build a following, I’ve been finding conversations. The discussions have contributed enormously to my writing, and have kept my on-line experiences very positive.

I haven’t encountered many people who know Frye, and fewer yet who were interested in his work. 🙂

I have been reading on your blog, and will return there soon. Perhaps Elke (a.k.a. the Subversive Elkement) will induct you into her “cult of spam poets” and we’ll soon be reading your work, too.

LikeLike

I also started to break down the public/private barrier. My experience with discussions on my own and other people’s blogs has contributed a huge amount to the ideas that go into the novel I am working on. I am always very glad to find other bloggers like yourself. I think that it is these interchanges that make the blogosphere what it is!

Frye and I were rather close for a while! Especially around senior thesis time.

I just checked out some of her spam poems and search term poems. I had never heard of that before! They are great. I might try my hand at it!

LikeLike

Welcome to spam and search term poetry.

I look forward to discovering your more of your influences.

Hutcheon’s essay on-line: http://www.library.utoronto.ca/utel/criticism/hutchinp.html

LikeLike

Thank you for the link! I am bookmarking it now!

LikeLike

Johannes, I agree to this “We look at the past nostalgically because it is clean.”

I liked your comment and I am following your interesting blog now – thanks again Michelle for pointing me to it!

I am a physicist and engineer, but I am enjoying my weird creative endeavors in the blogosphere (spam poems, search term poems…) more than I had expected. ‘Story telling’ has become a buzz word in the corporate world, too, and I was skeptical. Finally I do appreciate the power of the narrative over facts and figures. Which makes it harder actually for me now to write something very fact-y such as a technical report.

This was very random, too 😉

LikeLike

It makes for a hard truth, though! The past is only clean because of our mind’s natural inclination to narrativize. It is clean, yes, but constructed almost entirely.

I have been hearing more and more about spam and search term poems. I don’t really know what they are, but I am going to visit your page and find out!

LikeLike

I have another “time machine” related post to share, connected to the conversations that inspired this post: http://pairodox.wordpress.com/2013/05/08/fourth-dimension-surfing/

It answers the question, “How would a classical trained zoologist discuss time?”

LikeLike

Thank you for pointing me here! I just visited and left a thought.

LikeLike

Very nicely done indeed. I have been thinking recently (as have many, for a very long time) about the physical nature of our thoughts (let alone memory … a related topic for another day). When one ponders, considers, thinks, or contemplates … I wonder about the physical reconstruction of the brain which results, for a reconstruction it must be. Wouldn’t it be instructive to be able to quantify the difference between my brain as it was before I read your post and after I read it? Certainly there is something different about the before and after because the latter has more information than the former. Some say data are stored as newly constructed neural connections – OK, neural connections are electrical, and transient. So, I think what the experts are telling me is that new electrical connections are made between and among adjacent neurons and once the connections are made they can be made again (kind of like immediate conditioning perhaps). So, new connections ar registers which may be reaccessed at some future time. OK – but how do I retrieve any particular appropriate register rather some other? It’s all so confusing … but awesome. Questions such as these make the life of a materialist a challenge. D

LikeLike

I laughed very loudly with your last sentence, “Questions such as these make the life of a materialist a challenge.” I wonder, how many neural connections does it take to buy a pair of shoes?

What I’m beginning to question right now is how data I absorb from a source can remain as “the work of X” for a time, and I can neatly keep X, Y, and Z’s ideas separated and properly credited. However, once I relax that memory of where the information came from, it all starts to merge into one big, interesting tangle of ideas. My university training tells me to keep the ideas separated so I can properly attribute them, but the writer in me wants to see what will happen when I mix it all together. I wonder if there is a difference in the physical nature of different types of thinking?

LikeLike

What worries me about what you have outlined above is when we tangle together our works with those of other folks … and eventually we can’t tell the difference! D

LikeLike

Yes, it makes the concept of intellectual property tricky. 😉 I’ve discovered that being without these types of ‘ideas-based’ conversations for many years now, returning to them can be a lot of work, simply trying tracking down who wrote what or sourcing my influences. I forget the subtle differences of one scholar’s work from the next… and then, there’s always the concern that I might have thrown something ‘original’ into the mix, and have done some damage with misinformation. 🙂

LikeLike

I have once read that, when we remember the past, our brain actually re-constructs it. Even if we try to focus on facts in a neutral way, our memories are much more our own creations than recordings than we think.

In these investigations (I don’t remember 😉 the link any more) it was proved that we insist on remembering something as A while it was in fact B. So our time machines do not only take us back to the past, but to an alternative past universe.

LikeLike

Assuming the research sources that I hyperlinked have valid findings, then “truth” is a concept or theory we have yet to prove “true,” in a sense. Literal memory, remembering what exactly happened as a video would record information, is something we humans can’t have. Being locked into an accurate memory would cost us our hopefulness for the future and the ability to find creative solutions in the present.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this – I feel that there is a difference between truth and facts. Truth can involve speaking honestly about the way you remember something (even if it isn’t actually factual). In many ways, I believe truth is more valuable than facts.

Blessings.

Jen

http://thelilyandthemarrow.wordpress.com

LikeLike

I think so, too. I like the distinction you make between fact and truth. It’s a little bit like the difference between the details and the larger picture… facts can be the details that lead toward (or away from?) a larger truth?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on The Blogspaper.

LikeLike

Niiiice!! I talk about the glorious power of the mind in my “Sacred” series. In the older post on Solitary Confinement, I reflect on our inherent social character (referring back to your post) and what can happen when that’s take from us. You might chk out the new series on the impact of technology on learning also.

To make sure you don’t end up on a diff blog of mine, which has happened to people,

aholisticjourney.wordpress.com Diana

LikeLike

Your blog looks interesting, and I look forward to reading more of your thoughts on the efficiency of technology. My youngest daughter loved the Little House series, which has sparked a huge curiosity in her about life as a settler. We had a little farm for a while, so looking after animals and weeding a big garden didn’t seem very strange to her. I think the experience was very positive for our children, and I’m very curious to read more.

LikeLike

It’s funny, I was thinking about this very subject the other day. Does it matter if something really happened, or happened like that, if it reveals truth? Every writer should understand that fiction and non-fiction are only separated so we know where to find them in bookstores, and because of a human need to label and then weigh the merits of each label in a constant, but silent, battle about which is superior.

LikeLike

I really liked Mendelsohn’s article in the New Yorker (link in the post) for how he probes at this tension in memoir and autobiography. Sometimes I think we should label all writing fiction, almost as a means to end the categories. But then, that age-old statement, “truth is stranger than fiction” reminds me that some real-life stories would never make plausible fiction, never make it into those bookstores, and would never be shared.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on bermanj1forchange.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on LETHATECHNIQUE and commented:

For a writer, the failure of literal memory is a creative space in which possibilities emerge. After all, if I wrote a story about the significant symbols and metaphors of my life, without showing the reader how to adjust to my world or to learn how to relate, no one would understand my story. We simply would remain too autonomous to communicate, and yet, we are bound to a collective experience of life; language is the medium in which we meet. But before we enter this collective space, we must pass through the gap that effaces, for the moment, our singularity.

LikeLike

“For a writer, the failure of literal memory is a creative space in which possibilities emerge.”

A great and underacknowledged point.

LikeLike

Love all the video clips. Nice post.

LikeLike

Awesome post, dead on with your selection of videos and thoughts. Brought back a lot of memories of good times too! thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks. The videos were fun to add; I feel like I undermined my entire university education by failing to locate, source and properly document written text instead. 🙂

LikeLike

This is fascinating. Early Church history and Dr. Who in one breath! I used to keep a journal in college and I still remember the time I was in the middle of writing about my father when my childhood memories flooded over me and suddenly everything made sense. From that point on, my viewpoint changed and I became a very different person (a happier, more forgiving one). Reviewing our past to change our future… I completely agree. Thanks for posting this.

LikeLike

Thanks. This post grew out of contemplations on a similar experience. There really are some things we cannot understand when we’re children, and yet they effect us significantly enough that we remember them. We don’t change anything in the past by remembering it, but we can choose to understand differently. This gives us considerable freedom of choice for the future.

LikeLike

When remembering things, it is easy to paint ourselves as the hero of whatever narrative we have created. It is much harder to see ourselves as part of the overall truth.

I’m very impressed by the depth of topics and research going into this post.

LikeLike

Thanks. I think you’ve brought up the most difficult aspect of memory: we are always the protagonist of our own stories, yet we need to use some objectivity as well. (Or, at least, acknowledge that everyone has her/his point of view.) I’ll have to let these thoughts stew a while… there might be much more to discuss?

LikeLike

If only I had the time to remember the times that I have forgotten. This is a great read. A very centered view on temporal convergence.

LikeLike

Witty response–made me grin–thanks.

LikeLike

Memory is so important because the processes of memory are the processes of thought itself. Beyond this somewhat obvious fact, memory is the means by which we contemplate truth of self through the ingathering of time. And there is nothing more important than honesty as a writer. St. Augustine writes,

‘In that vast court of my memory…. meet I with myself, and recall myself, and when, where, and what I have done, and under what feelings. There be all which I remember, either on my own experience, or other’s credit. Out of the same store do I myself with the past continually combine fresh and fresh likenesses of things which I have experienced, or, from what I have experienced, have believed: and thence again infer future actions, events and hopes, and all these again I reflect on, as present.’

My favorite writers are T.S. Eliot, Dante, and Joyce. Eliot’s conception of memory throughout his oeuvre (but particularly in Four Quartets) aligns perfectly with St. Augustine’s. Eliot supplements St. Augustine’s theory of memory in stating that it represents the necessary modality for contemplating ‘the still point,’ which I believe, is the intersection of personal and collective, or historic, memory. If I get too far into this I may never stop. In any event, Joyce, Eliot, and Dante were all deep readers St. Augustine and I believe these quotes of Augustine’s are applicable to all their works and also your post. Thanks a lot for this awesome post!

‘[While reciting a psalm] my faculty of attention is present all the while, and through it passes what was the future in the process of becoming the past. As the process continues, the province of memory is extended in proportion as that that of expectation is reduced, until the whole of my expectation is absorbed….’

‘What is true of the whole psalm is also true of all its parts and of each syllable. It is true of any longer action in which I may be engaged and of which the recitation of the psalm may only be a small part. It is true of a man’s whole life, of which all his actions are parts. It is true of the whole history of mankind, of which man’s life is a part.’

‘For memory retains the past by recalling it, the present by receiving it, the future by foreseeing it. It retains the simple, as the principles of continuous and discrete quantities—the point, the instant, the unit—without which it is impossible to remember or to think about those things whose source is in these.’

LikeLike

John Mendelsohn’s essay for the New Yorker, as linked in the post, discusses St. Augustine’s memoirs and the influence he’s had on autobiographical writing. I learned that St. Augustine’s writing was motivated by a need to contemplate an act of theft which he committed when he was young, and to explore the troubled feelings this had caused him over his life. I’ve had only one encounter with Augustine, about 14 years ago in a class on rhetoric, in which we discussed On Christian Doctrine: Book IV.

What has stayed with me all these years–and this had a tremendous impact on me–is that writing must call forth compassion from within the writer, as well as the reader. I’ll need to do more reading, but I suspect that the concept of compassion might be the ‘still point’ which you connect to the ‘intersection of personal and collective, or historic, memory.’ Does this seem plausible?

Augustine’s writings in the essay I mentioned were very focused on a responsible use of rhetoric; he carefully describes the humility and purpose required of those who use words. In essence, we must as writers (be aware of and then) surrender our desires to become open to something larger than our own immediacy and needs. When we do this, we use all the powers of our rhetoric to entertain, engage, teach and guide our readers into that same compassionate connection that we have been given opportunity to express.

It is a significant compliment to have received your comment, and to have St. Augustine’s writings invoked in this discussion. Thank you for taking the time to share your thoughts.

LikeLike

I am not sure this had been freshly pressed when last I was here! Congratulations! I am so glad this one got exposure –it really had me thinking!

LikeLike

It wasn’t… which means your comment added to the reader experience. Thanks! Now I’m going back to finish reading your response to cyborgs on your blog.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on leanworkspace blog.

LikeLike

Congratulations on being freshly pressed. This piece definitely gave me much to think about

towards my own life and work.

LikeLike

Congrats on being Freshly Pressed! I think we re-write our memories all the time, collectively and as individuals. I find it all the time in the writing I do, and I think your point about writing living at the intersection of memory is quite true.

This, to me, is how historians here in NZ have got away with almost completely re-writing our past in the image of the present they wish for, a process that has been going on for the last 30 years or so. Much of it is nonsense by any empirical measure – the classic is the notion that New Zealand’s Maori invented trench warfare and it was then stolen by the British for the First World War, which is absurd. A quick glance at any childrens’ book on the history of warfare suffices to show up the falsity of that argument – and yet it has been seriously upheld as a ‘truth’ at the highest academic levels here, to the point where any effort to question it is not merely viewed as wrong, but taken as an attack on the status of those promoting the argument.

I have no doubt that this local experience is reflected in similar examples around the world. As the lead character of my favourite all-time SF show tells us, ‘time can be re-written’. And so it has been – without, even, any help from a TARDIS!

LikeLike

Hi Matthew, thanks for commenting; I was wondering what your thoughts would be on this topic. In consideration of what you’ve written on your blog, the question of history and how we rewrite it was on my mind when I was composing this post.

I’ve also noted a significant revision of the recent history of where I live, on the Canadian prairies. The area opened to settlement in the mid 1890’s and for a period of the first 20 – 25 years of settlement, homesteading became increasingly restrictive, limiting who was allowed to own land on the prairies. As children in school, we never learned about this aspect of prairie settlement, how some groups of people were excluded entirely from citizenship in Canada, or how others were granted homestead rights only to have them revoked later. What seems to be happening in the story-telling now is that the bias that was prevalent throughout the dominating culture of the time is now being transferred to particular individuals, as though they were fully responsible for the most embarrassing acts of mistreatment and abuse of power. There seems to be a scapegoating process unfolding in the story-telling that cleanses the larger community and excuses them from blame. I suppose doing this also reduces social responsibility and avoids accountability now (i.e. compensation for property which was seized from individuals such as the Doukhobors, First Nations People, Chinese immigrants, etc.). At least, this seems to be the most plausible explanation for the huge inconsistencies of information….

I don’t mind that there are creative spaces in the failure of memory, but when this is accompanied by a lack of responsibility, I worry about what will result. It seems much like the symptoms of mental illness, to be delusional.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on desaxesblog and commented:

le temps n’est jamais perdu…

LikeLike

I don’t know, but I have a feeling that you are a great writer. I think you will be one of my great idols in terms of philosophical writing. It makes me anxious while reading your brilliant lines. Indeed, I need more practice in writing.

LikeLike

I’ve just been to your blog, and I really enjoyed your recent fiction post. You also have a significant personal story you are telling. No need to feel anxious, and do keep writing. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks! I’ll post some of my fiction work soon. 🙂 I really admire your writing. Have a great day always:-)

LikeLike

Drawing on past experiences is a wonderful tool and contrasting that with future things that may happen is what gets me going. What would happen to a well known writer that finds himself suddenly dropped in the past? Would the lack of modern conveniences deter his finishing the greatest novel ever written?

LikeLike

Interesting questions. I suppose the writer would know from his future-past if he finished the book in is past-future?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Jusd.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Pahto's Shadow Online.

LikeLike

This probably has been the most intresting article on writting Ive ever read. The so called truths we own in out mind are subjective to how we remember them. To remember them is like to live them all over whoever I cant help but feel we continously have wishfull memories added not only each time we tell a story but also each time life is relived. Thank you for the thought provoking script look forward to reading it again tommorrow!

LikeLike

I agree–wishful thinking is both necessary, to some extent–and dangerous. I suspect we need to cultivate a balance which leads us to living with ourselves and our imperfections, and being honestly accepting of who we are. It’s very hard work, but I believe the rewards are worthy of the task…. and it’s work that never ends, either! (meaning, constant rewards?)

LikeLike

Howdy! Would you mind if I share your blog with my facebook group?

There’s a lot of people that I think would really appreciate your content. Please let me know. Many thanks

LikeLike

Sharing is fine, thank you for asking… do you have a public link to your facebook group?

LikeLike

Interesting post – I suppose I somewhat expect the individual writer to bend their memories to the emotions that they felt at the time of the memory as well as how those emotions may have changed over time. What disturbs me is systematic rearranging of the facts of history to suit a current political or sociological mindset. That smacks to me of the early etymology you spoke of where memories were not being handed down but changed to protect the speaker. How changed would the following generations be based upon the “new” truth rather than the actual truth? Perhaps this has to do with the innate human need to process the facts around us in the lens of our own vision of truth.

LikeLike

Yes, I wonder about the conflicts between the natural process of developing inaccurate memories and changing our stories for our own wants or needs. When this happens, I think it has the potential to create an uneasy society that follows. Much like a dysfunctional family that guards its secrets, the next generation becomes prone to anxieties it doesn’t understand.

For those who have had experiences like this, of sensing fragmented truths they cannot reconcile, the storytelling processes can feel quite pained. I’m so often surprised by how many writers and artists have experiences of fear and anxiety within their work. It seems very common to be afraid of lying as we tell our stories. This certainly worries me. Sometimes the fear that I’ll fail to be truthful can hold me silent even more effectively than the shame of what I might expose.

LikeLike

If each generation could find the foundation, the bedrock, the basis of why they exist, it could be as a “re-set” button to keep mankind from deviating away from truth. This is a tall order, I realize, but for me, it all comes back to the uniqueness and the value of life – and I quote Wordsworth here – “Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting; the soul that rises within us, our life’s star, hath had elsewhere its setting and cometh from afar. Not in entire forgetfulness, and not in utter nakedness, but trailing clouds of glory do we come from God, who is our home.”

LikeLike

I was looking at your blog just now. I wanted to see if I understood the re-set button as you use it; I’ve called it a correction line, which is something you probably don’t have in California. On the prairies, the land was surveyed into 160 acre grid parcels, called quarters. A section of land is comprised of four quarters, and each section has road allowances on each side. Square grids don’t fit neatly on to the spherical earth, so to keep the lines in a tidy north-south or east-west orientation, the roads must be jogged at regular intervals. We call these jogs correction lines, which keep travellers on course. We lose a little speed and a little time when we must bend with the line, but they are necessary if we ever hope to get where we’re going. Life seems to have a similar process; we move for periods of time in a fairly steady course, but there are regular correction lines, too.

Lately, I’ve come to understand this process to be something like maturing compassion, of learning one’s limits while embracing one’s responsibilities. Your writing resonates with me in this regard, and I look forward to reading more.

LikeLike

What a great picture of staying on course – a correction line – and yes, I agree with you, the process is a maturing compassion and the growth maybe painful but well worth it,

LikeLike

I agree–painful but worth it!

LikeLike